Akan and Baule Headdresses

Headdress of an Asante Herald/ Royal Crier (Nsɛneɛfoɔ), who as a scholar, among other things, has the task of carrying the messages of the king (Asantehene). Asantehene's procession may well precede the procession with a dozen heralds at the head of the train wearing a typical headdress of colobus hide adorned with a large rectangular plate of drifted gold (repoussé) and silver chain. Published: Blum, Rudolf (2007). EX collection Rudolf and Leonore Blum. Volume 2 B. Zumikon: No. 38. #asante #akan #mooscollection

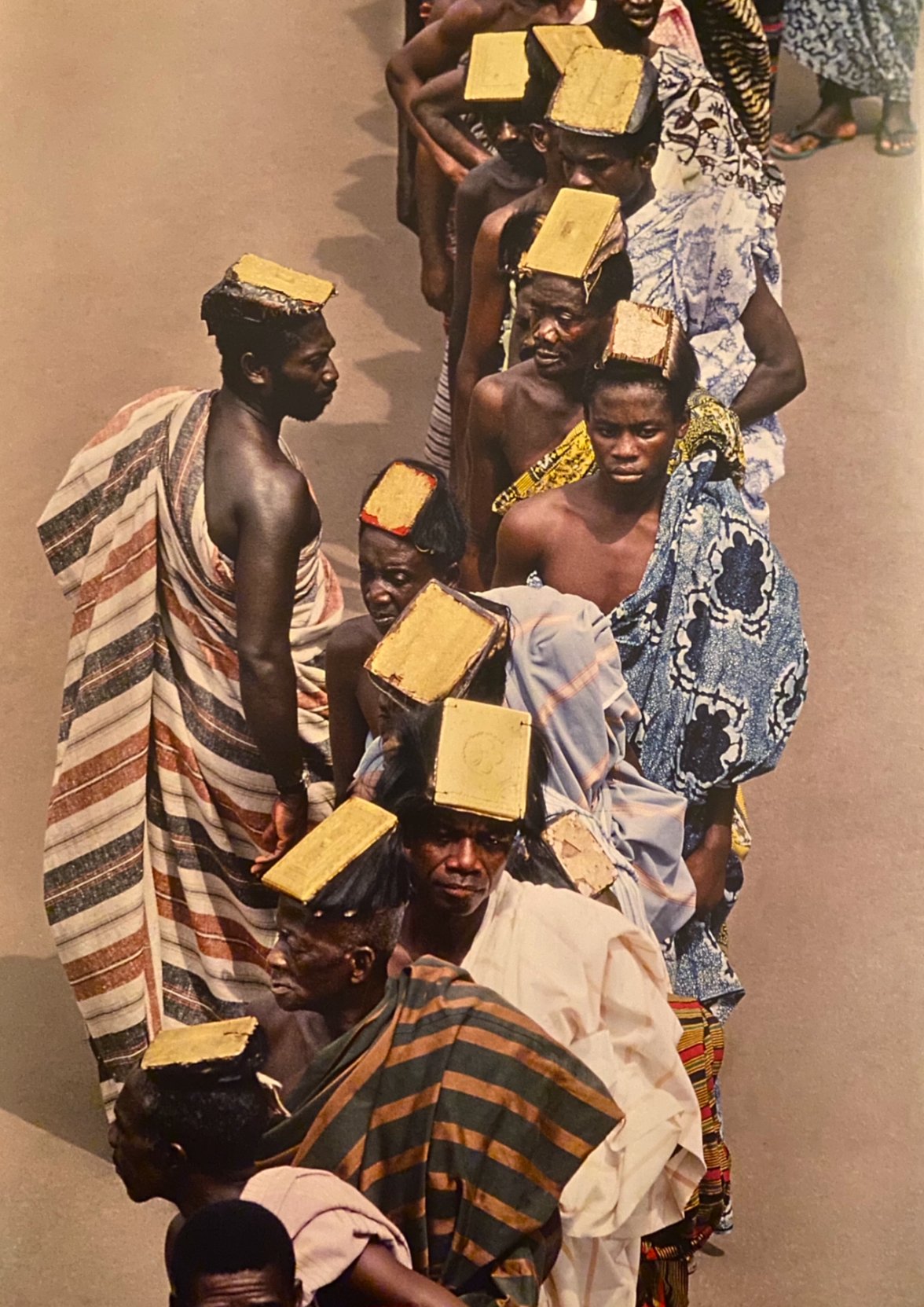

A procession of Asante Heralds/ Royal Criers (Nsɛneɛfoɔ). Photo credit: Lüthi, Werner & David, Jean (2009). Exhibition catalogue: Helvetic Gold Museum Burgdorf. Gold in West African Art. Zurich: Galerie Walu.

A Nsɛneɛfoɔ Royal Herald with the Nsɛneɛfoɔhene in the background. The Nsɛneɛhene is the highest ranking of the Nsɛneɛfoɔ and is usually identified by the conical headdress made of white fur instead of the black with three plates of gold. Photo credit: Lüthi, Werner & David, Jean (2009). Exhibition catalogue: Helvetic Gold Museum Burgdorf. Gold in West African Art. Zurich: Galerie Walu.

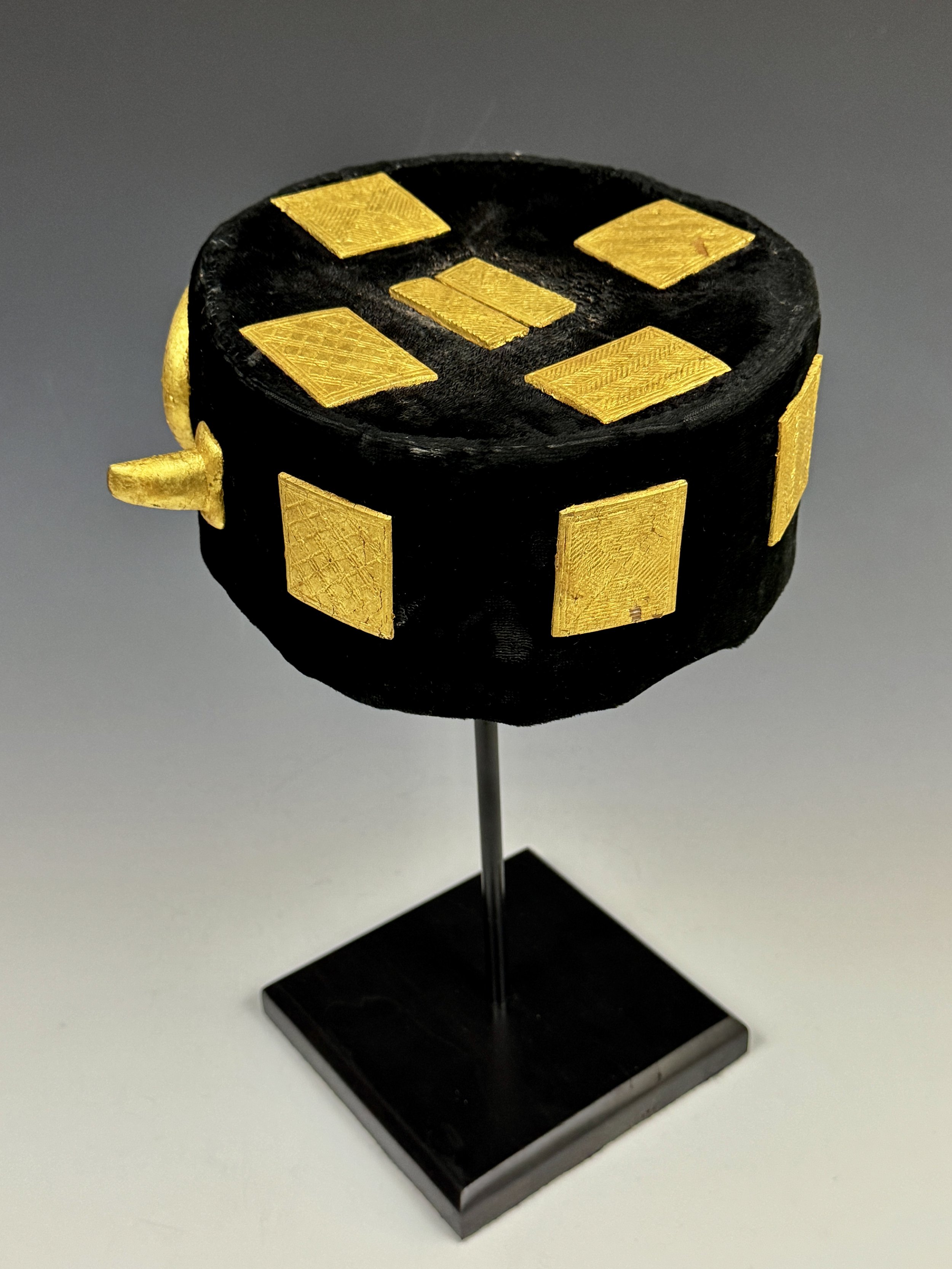

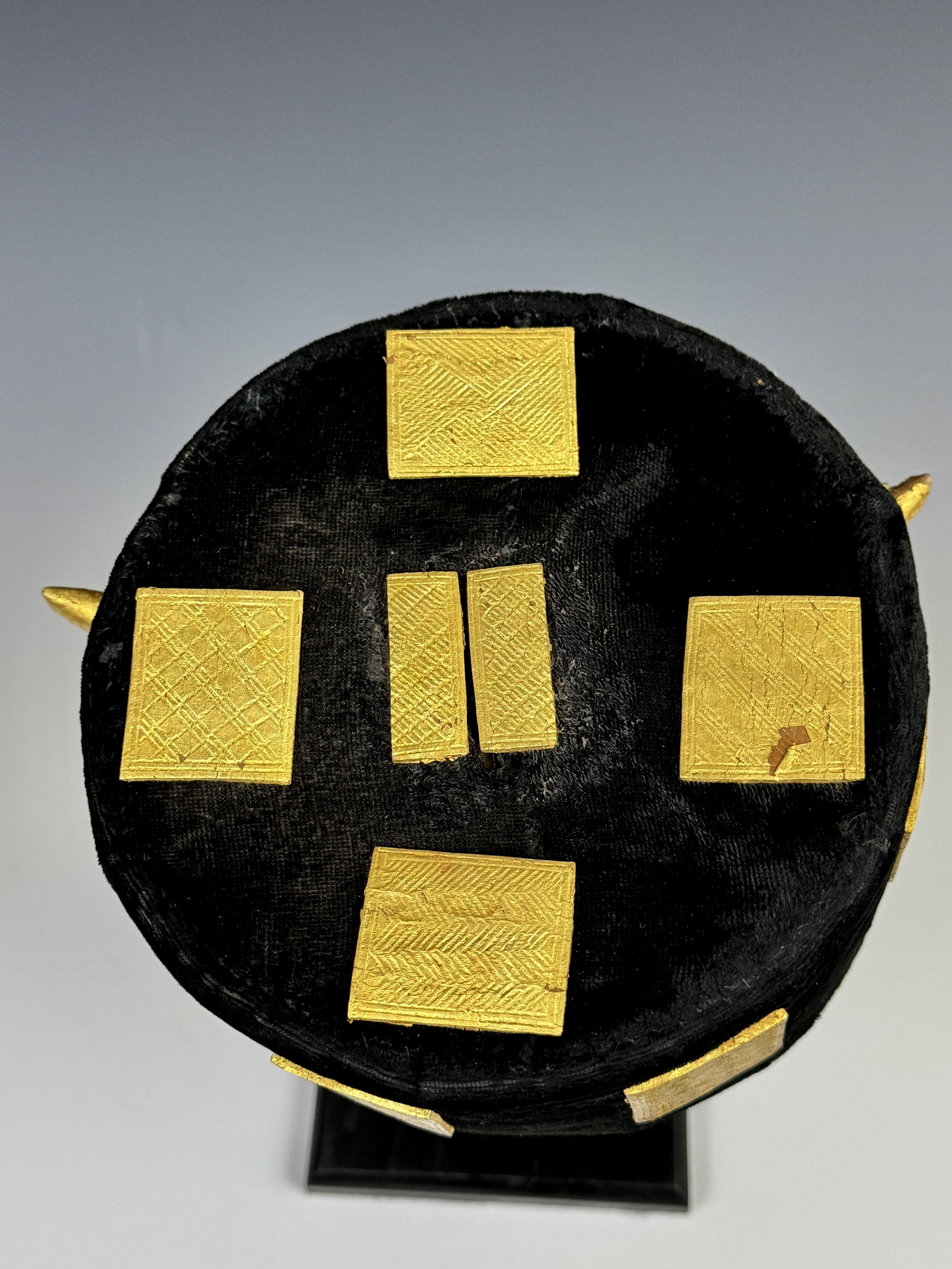

Akan Headband, "abotire", Côte d’Ivoire Material: velvet textile, wood, gold foil. Ø 24 cm. The abotire headbands, commonly referred to as crowns, are worn by regents at ceremonial festivities as a sign of rank and allegiance. The velvet abotire (headband) is the most common of the many Akan crowns. Worn across the forehead, the band is decorated with gold-leafed ornaments with symbolic and proverbial meanings. Here, the band is covered with a row of decoratively carved rectangles, each flanked at top and sides by triangles. Together, the shapes form the Maltese-style cross shape of “musuyideɛ”, a symbol that protects from curses and bad luck. The two short vertical projections at the back are called “bongo’s horns”, a reference to the spiritually powerful forest antelope. #akan #mooscollection Published: Lüthi, Werner & David, Jean (2009). Exhibition catalogue: Helvetic Gold Museum Burgdorf. Gold in West African Art. Zurich: Gallery Walu. Page 33 Exhibited: Helvetic Gold Museum, Burgdorf (2009).

The Asantehene Nana Otumfoe Sir Osai Agyemang Prempeh II (King of Asante) shown here in regalia wearing a similar abotire "crown" with the Maltese-style cross shape of “musuyideɛ”, a symbol that protects from curses and bad luck.

Asante headband, Ghana. The Akan headbands called abotire, commonly referred to as crowns, are worn by regents during ceremonial festivities as a sign of rank. Stars are sewn onto the velvet ribbon. These motifs, carved from wood and covered with gold leaf, allegorically stand for sayings that refer to the praiseworthy qualities of the wearer. For example, the saying "The evening star, always full of longing to marry, always stays near the moon" refers to the regent's loyalty to his people or his wife.

The carved wood and gold leaf objects circling this chief’s abotire “crown” are shaped like a multipetaled yellow flower called fofoo. “The highly conventionalized maxim associated with this form is said to deal with issues of envy and jealousy, “What the fofoo plant wants is for the gyinatwi seeds to turn black.” The proverb is another example of the Akan penchant for the close observation of natural phenomena. The connection with jealousy, however, is not entirely clear. Do the seeds envy the flowers for their beauty? Do the flowers envy the seeds for their curative properties? Or perhaps the name of the plant is another example of Akan wordplay where fofs is the Akan verb for “to cherish”. This motif also is seen in other Akan regalia items as well as akrafokonmu or soul washer’s discs.

Two of my favorite Baule items in the collection are skeuomorphs, objects in the same shapes as the originals, yet carefully carved from wood with intricate surface designs. Gold leaf covers the pith helmets, an indication that they were display objects. Côte d’Ivoire. Early to mid-20th century. The Baule notables appropriated images from European colonial origin associated with prestige, power, and authority. Among them are crowns and pith helmets. These items were worn and displayed in special functions to project rank, authority and importance. - Provenance: Galerie Walu, Zurich. René and Denise David, Kilchberg. Denise Zubler (1928-2011), Zurich (2000). Zubler community of heirs (2011). Published: Quarcoopome, Nii O. (2010). Through African Eyes. Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts. Page 74 and 258, catalog no. 73. Lüthi, Werner / David, Jean (2009). Gold in the art of West Africa. Burgdorf: Helvetic Gold Museum. Page 33. Exhibited: Helvetic Gold Museum Burgdorf. "Gold in West African Art" (2009). Detroit Institute of Arts. "Through African Eyes"

A coastal Akan chief’s crown, Shama region, Ghana. (fabric, wood covered with hammered gold foil, seashells covered with hammered gold foil.) The Akan chief’s head gear regalia, commonly referred to as crowns, are worn by chief regents during ceremonial festivities as a sign of rank. This crown has British Isle influenced imagery displaying a series of carved wood and hammered gold foil thistle flowers associated with Scotland, British military, and the royal family. The image would have been commonly seen on military badges and medals like the “Order of the Thistle”. There are small seashells covered with gold foil in between the thistles. The crown is topped with a step pyramid motif covered with gold foil.

Asante chief’s regalia “crown” shown here with a fly whisk from the same chief's regalia. The chief’s “crown” is strongly influenced by European heraldic symbolism with a combination of Akan symbolism. The pineapple finial said to represent sovereignty to the Akan in chief’s regalia can also be interpreted as the pineapple takes time to mature and won’t be sweet if eaten early — a statement on the patience of the chief. This can also be seen as patience for selecting an accomplished and experienced chief. Encircling the crown with the fleur-de-lis symbols from European influences are fern fronds called “aya”. The meaning of the image is derived from an Akan word play on fern “aya” where the word ya or yaw means insult or rebuke. When seen in regalia the meaning is “the chief does not fear insults”. The fly whisk is another important part of the chief’s regalia and a chief still carries a horse tail whisk in his left hand when he is in procession. A proverb for the horse tail fly whisk is “If the horse does not go to war, its tail does”. The tail is considered a charm to help bring victory. Ex Morton Dimondstein, Los Angeles

Akan Headband, “abotire”, Ghana. This stunning “crown” is made of a strip of woven kenté cloth sewn to other textiles and covered with consecutive rows of the adinkra symbol “musuyideɛ“ covered with gold foil. The abotire headbands, commonly referred to as crowns, are worn by regents at ceremonial festivities as a sign of rank and allegiance. The velvet abotire (headband) is the most common of the many Akan crowns. Worn across the forehead, the band is decorated with gold-leafed ornaments with symbolic and proverbial meanings. Here, the band is covered with a row of decoratively carved rectangles, each flanked at top and sides by overlapping triangles. Together, the shapes form the Maltese-style cross shape of “musuyideɛ”, a symbol that protects from curses and bad luck. The two short vertical projections on the sides are called “bongo horns”, a reference to the spiritually powerful forest antelope.

A chief’s crown (most likely coastal Akan states of Ghana). In the Akan states, the chief crowns and other headwear, aside from the abotire are in the category “kye”. Similar to the abotire the entire top is enclosed and is covered with amulets made of wood and gold foil.

A Baule or Akan (Baoulé) “abotire” chief/dignitary’s head band—felt, fabric, wood, gold foil. Côte d’Ivoire.

A Baule or Akan chief’s crown from Côte d'Ivoire. Fabric, wood covered with gold leaf. The chief crowns and other headwear, aside from the abotire are in the category “kye”. Similar to the abotire the entire top is enclosed and is covered with amulets made of wood and gold foil.

A Baule or Akan (Baoulé) “abotire” chief/dignitary’s head band—felt, fabric, wood, gold foil. Côte d’Ivoire. This example is missing one of the "bongo horn" ornaments on the right side of the headband.

The three similar Baule (Baoulé) or Akan“abotire" (open top) and "Kye” (closed top) chief/dignitary’s head bands as a group—felt, fabric, wood, gold foil. Côte d’Ivoire.

An Agni chief in the village of Essikro, west of Bondoukou wearing a similar abotire. This was taken a week before the coup d'état in which President Bedie was removed from power. Photo: Dean Hamerly